In the first of a series of short articles looking at space missions I wanted to start with a brief introduction to the Cassini Mission to Saturn. When I worked at Queen Mary, I had colleagues who enjoyed regularly talking about their research. One of my favourite people to listen to talk about their work is Professor Carl Murray. Carl is in the School of Physics and Astronomy and is the only UK member of the Cassini Imaging team. He is interested in the rings and moons of Saturn, specifically the F-ring. He has been involved in discovering new moons of Saturn and recently there has been broad coverage of the discovery of a moon during its birth – really exciting stuff! His enthusiasm for discovery is infectious and whenever I leave his office I always find myself thinking about ways in which I could still go on and complete a PhD, not to get the qualification, but to get that feeling of discovery. Carl successfully uses the tools on the Cassini spacecraft to discover more about the behaviour of the rings and moons of Saturn.

The Cassini spacecraft launched in 1997 and arrived at Saturn in 2004. In addition to the orbiter, there was a lander called Huygens which touched down on the surface of Saturn’s moon Titan. The UK has strong involvement with both the science investigation and the instruments. In addition to Carl there are scientists such as a Michele Dougherty at Imperial and John Zarnecki at the Open Uni. The instruments on board include a camera system, magnetometer, dust analyser, radar and various spectrometers. Full details here.

Astrophysics is a brilliant science. However, it’s a bit different to other sciences in that we have to observe the evidence available. We can’t just build a star of planet and wait to see what happens. We have to use telescopes and spacecraft to find answers. Cassini is helping us to use Saturn, its rings and moons as a laboratory to discover more about how planets are formed as it’s essentially a miniature solar system.

There are many other benefits gained along the way from the money spent on the mission. This includes technological advances due to miniaturisation of instruments like camera systems (Cassini’s cameras are 1 Megapixel – much smaller than any current mobile phone camera – but at launch, the technology was the best available) and inspiration of school pupils using the science of Cassini. Since the mission began, school pupils across the world have been able to participate in the Cassini Scientist for a Day competition to take control of the spacecraft by making a scientific argument for which target should have its picture taken. This process mirrors that used by the scientists to plan what Cassini will do in its time around Saturn and the schedule of observations is set out months in advance.

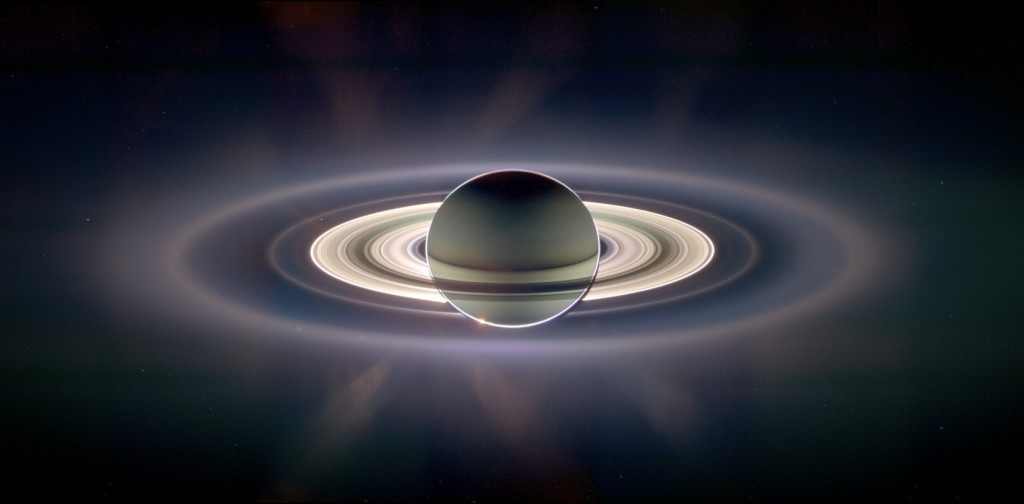

I regularly speak in schools to both primary and secondary pupils and teachers and whenever I get the chance I always show them this image taken by Cassini:

In fact, it is a mosaic but there is an interloper: Earth. This is one of only 3 images taken of the Earth by a spacecraft from elsewhere in our Solar System – do you know what the other two are? We can see in this next image that we have focussed on the picture containing Earth and in the corner we have zoomed in further. The smudge on the top left hand side next to the blob that is Earth, is the Moon.

This is my favourite space image as it gives me a great sense of scale in the universe and shows how small we are and how much there is left for us to explore. I can’t wait!

The Cassini mission is due to complete in 2017. The most likely fate of the spacecraft is going to be a controlled plunge into the atmosphere of the planet but I know that before then there is still a great amount to be learned from this fantastic spacecraft.